In search of documents on the history of the Vieux Château, I visited the official archives in Nevers, together with Christian de Grandpré, our neighbour and the hereditary owner of the Châtellenie in Corvol.

The impressive contemporary building houses the collected historical archives from across the Nièvre department, and, in good French bureaucratic tradition, employs a dedicated team of staff whose job it is to curate the material and respond to obscure requests by curious amateur historians such as myself. Christian and I found ourselves alone in the reading room.

I had corresponded with the chief archivist earlier, while the archives were closed to the public, and he had alluded to some promising sources which I would be welcome to consult.

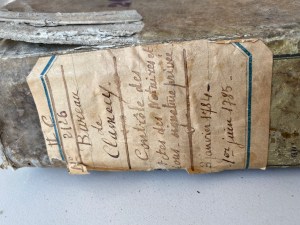

With the assistance of one of the archivists, I identified the reference numbers for the files that concerned Corvol, and, ten minutes later, a heavy cardboard box appeared and was handed over to me.

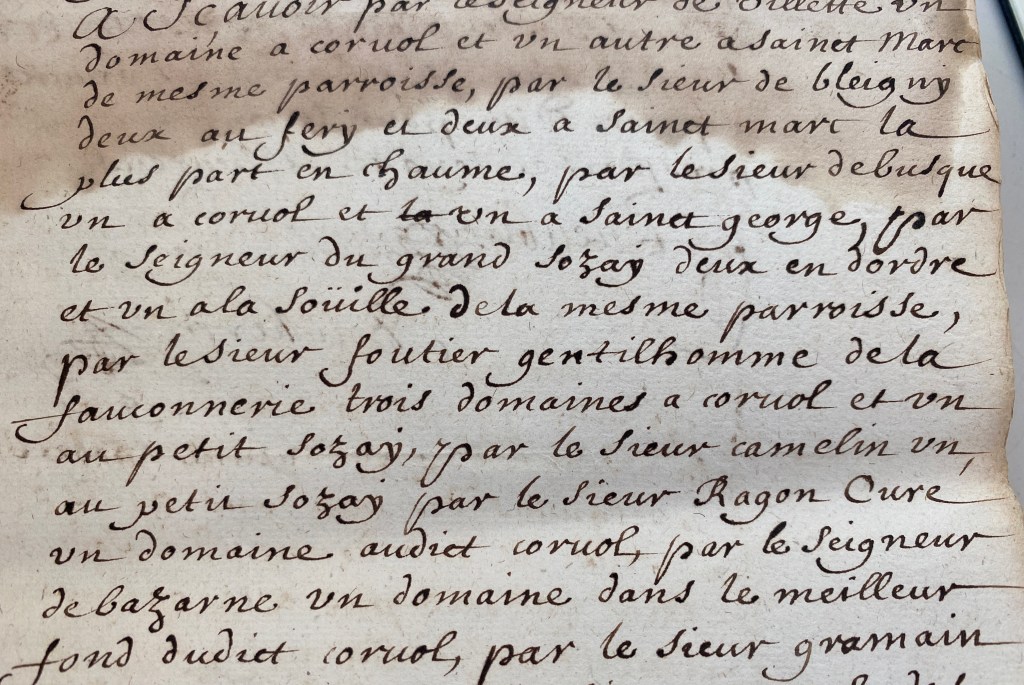

The large fabric strap of the box untied to reveal a stack of hand-written notarial records and court decisions from the 16th and 17th centuries, nearly all related to disputes and successions in the village. The thick, jagged-edged cream parchments were surprisingly well-preserved, each covered with formal black cursive script, as dense and impenetrable to the untrained eye as a secret code. Slowly, I deciphered the sense of some the documents, gaining glimpses into the conflictual and legalistic realities of the French Ancien Régime, and some of the local disputes in Corvol.

A particular highlight was a lengthy document detailing a court case brought by the inhabitants of Corvol. It appears that in the early 1700s, one of the owners of the Château de la Porte, François Foutier, Gentilhomme de la fauconnerie de France, had a somewhat exaggerated understanding of his prerogatives as a ‘Seigneur’, and usurped lands and shot at the pigeons of his neighbours (an extremely valuable asset at the time).

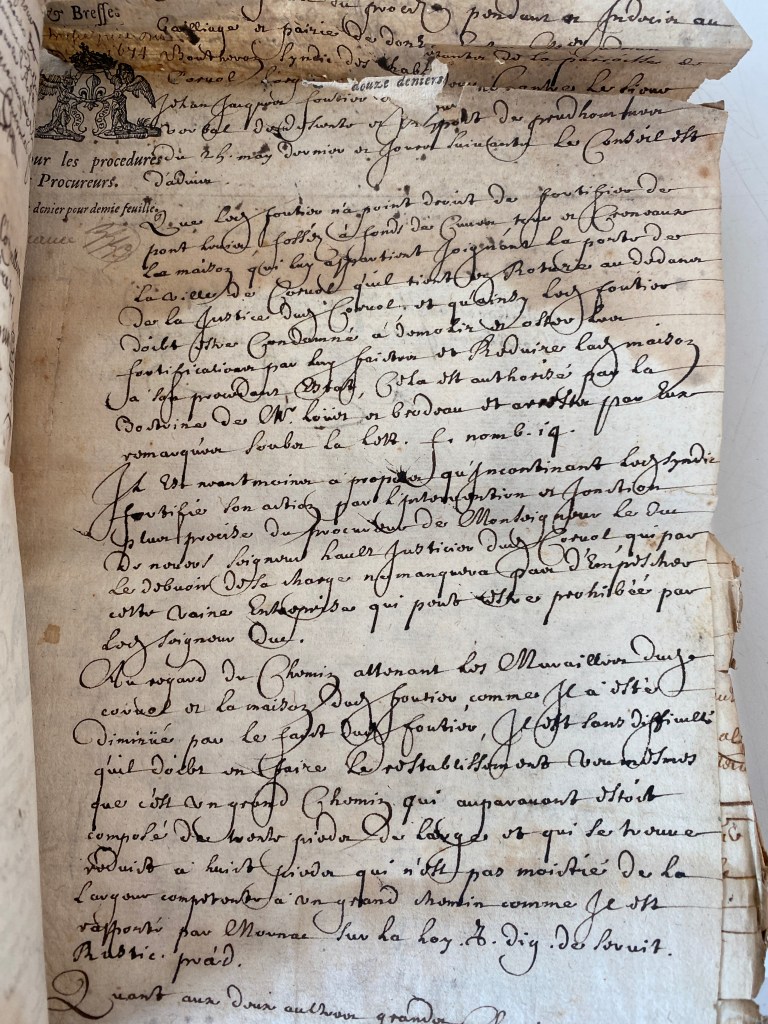

So ambitious was Sieur Foutier that he set about fortifying the château, in defiance of all communal rights and regulations. The fortified house was made to look like a medieval castle, with towers, moats, drawbridges, battlements, etc., and even a private road leading to the house from the town gates was planned, with turrets marking the passage. All of this was built along the village walls. We do not know how much of his ‘dream house’ Sieur Foutier was able to build, but his project ended in a lengthy legal entanglement with the local community, and his eventual condemnation by the higher courts.

Another document refers to a certain Jean-Jacques Foutier. Was this François Foutier’s son or heir? In any case, Jean-Jacques also seems to have played rough and hard with the local commoners, as the proceedings of his court cases show. Further investigation of these precious archival boxes will assuredly reveal more surprises.