In the beginning, it was all quite simple. Armed bands marauded the countryside, and built themselves fortified bases to assert their power and to protect themselves from other warlords. The man (as they usually were) who wielded his strength most effectively became the ‘seigneur’, or lord.

Together with the authority that came with force came the right to reward faithful companions with privileges, properties and houses, in return for loyalty and service. In turn, the seigneurs maintained their own privileges in return for obedience to the king. The feudal system was born.

(Aveu à René, 1469)

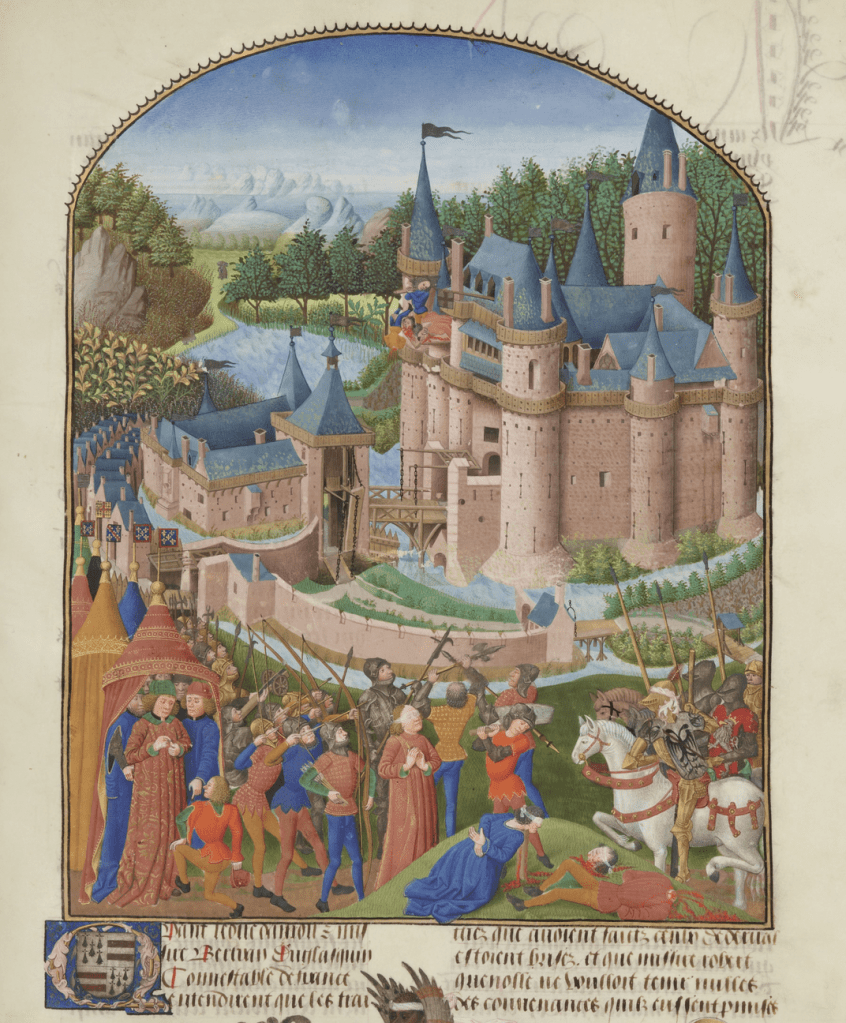

Lords and princes lived in fortresses or strongholds. Until the XIV century, the term ‘château’ (castellum in latin) or castle in English, referred in a general way to any fortified building or town with a defensive wall. Gradually, the term château was used to signify the fortified residences of the seigneurs, in contrast to the ‘maisons-fort’ or manors of the landowners.

The language of fortification, originally related to military power and service in war, progressively became associated with nobility, and fortifications became associated with the nobility’s economic and juridical power. Nobility implied privileges and was expressed in such things as clothing – including the right to carry a sword – and architecturally: the château.

The status of the nobility evolved progressively over the centuries. By 1404, the nobility was sufficiently powerful to demand, and be granted, exemption from the principal tax, on the grounds that they would fight for the king in times of war. In the early Middle Ages, all nobles legally and juridically enjoyed the same privileges. In practice, the power of a noble was related to their seigneuries and the privileges of each particular fief. For example, only the seigneur could build a ‘colombier’ or dovecote (whose occupants enjoyed the pick of the local peasants’ crops) and hunt game on their lands. Depending on the lord’s importance, he was granted the right to administer higher, middle or lower justice, with the authority to punish (commoners), from the death sentence to simply imposing fines.

Architecture was related to the status and privileges of the individual seigneur. The right to have an entirely fortified castle, with towers and drawbridge, for example, was limited only to the lord with the highest privileges.

Following the end of the Hundred Years War (1337-1453), the need for fortified castles was no longer a priority. By the Renaissance and well into the XVIII century, the French kings, soon imitated by their vassals, decided to build or adapt their châteaux from the medieval defensive strongholds they had once been to comfortable palaces.

As the power of the monarchy grew, and the State was consolidated, the independence of the local nobility was progressively reduced. By the XVII century, not all ‘seigneurs’ were nobles, and not all nobles were lords with châteaux. Indeed, it was more often through the acquisition of a handsome property that one accessed a title and the status of the nobility, despite an edict of Henri III in 1579 expressly opposing this development.

Unlike in England at the same time, the title of a noble family was related to property which was, in theory, lost if the property changed hands. By the XVIII century, a growing number of families attributed themselves titles related to their properties – as long as these were not duke or prince, a privilege only granted by the king in person.

As successive monarchs sought to consolidate their power (and fill their coffers), the right to titles became a privilege which could even be bought and sold. As titles were distributed by the king, the newly-enobled person would seek to obtain or build a château – and add the all-important ‘particule’ to the geographic location of their estate.

The Revolution brought a temporary end to the feudal system. Many châteaux were pillaged or burnt down, their owners guillotined and the property of exiled aristocrats was confiscated. Under the Napoleonic regime and later in the 19th century, some properties and privileges were partially restored, and the nobility survived as an intrinsic part of the ruling classes, marrying into the economic elites to preserve its fortunes.

Today, there are as many as 45,000 châteaux of various sizes and importance in France, 11,000 of which are classified as historic monuments. A few of these vestiges still belong to the same family, despite the vicissitudes of history, but the great majority are owned by organizations or companies, or by proud new private owners.